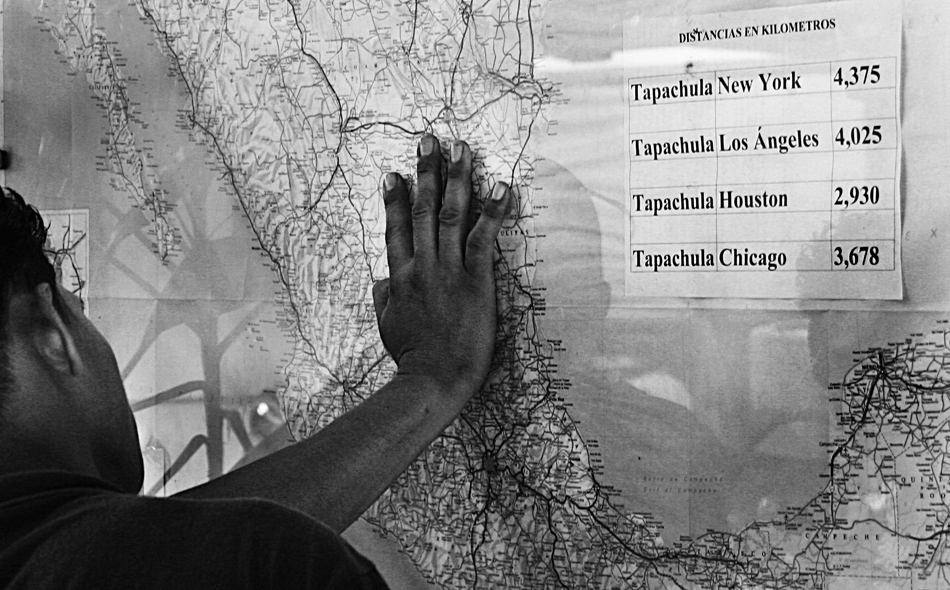

The migrant route is path through which hundreds of thousands of people attempt to cross Mexico’s territory each year in the hope of reaching the United States border. These paths are the setting of one of the most severe, extensive, and yet unnoticed humanitarian crises in the hemisphere. The route encloses a macabre reality that affects not only the souls that traverse these pathways, but our entire hemisphere—populated by “potential migrants”—which all too often ignores the deadly dangers of migrating.

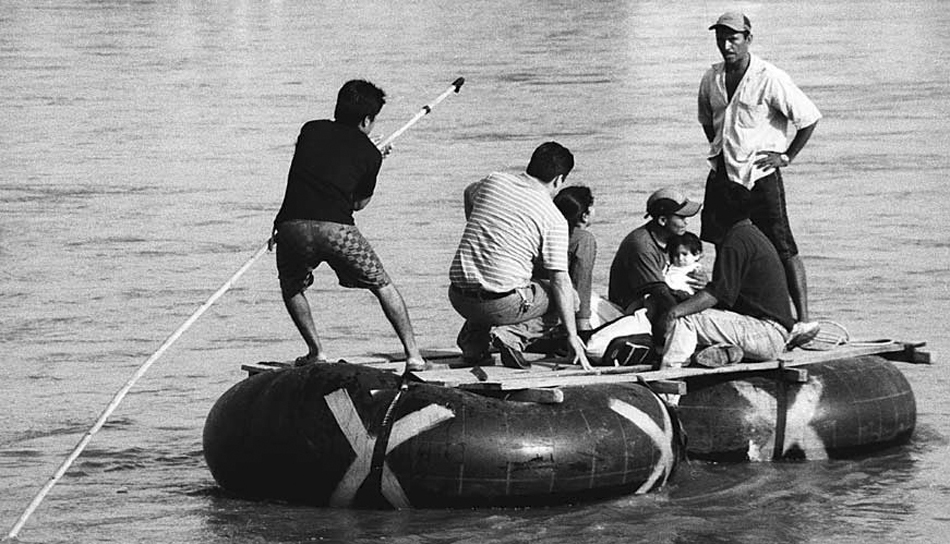

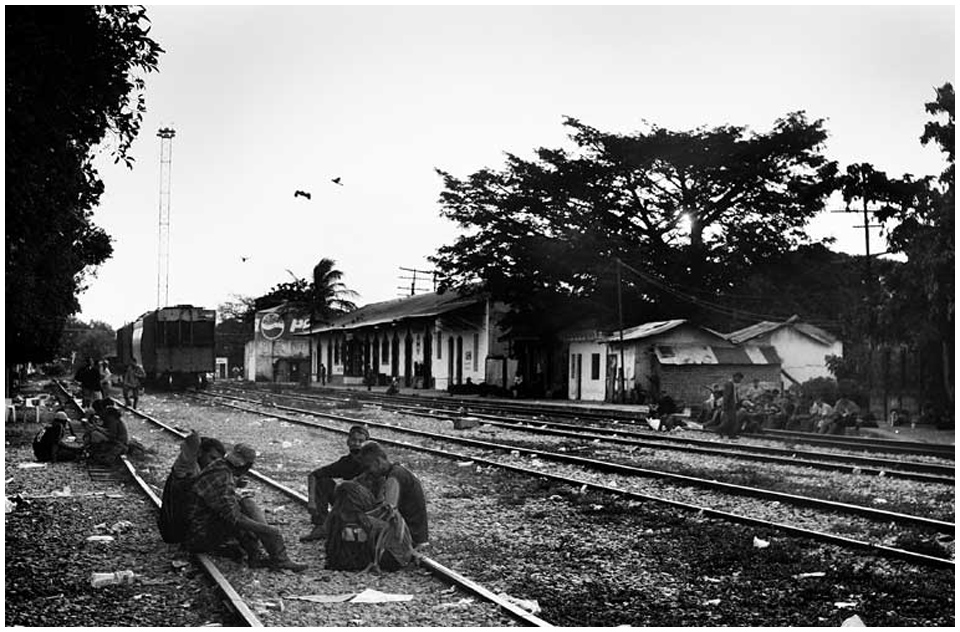

Since the early 1990s, Mexico has served as a barricade against the hemisphere’s migration to the United States. Due to an extensive web of migration control posts throughout Mexico, road travel for undocumented people has become practically impossible. Even so, migration continues. The country’s failed attempt to impede the overwhelming human flux from the south has merely confined these migrants to the most inhospitable trails and deadly means of transport in Mexico.

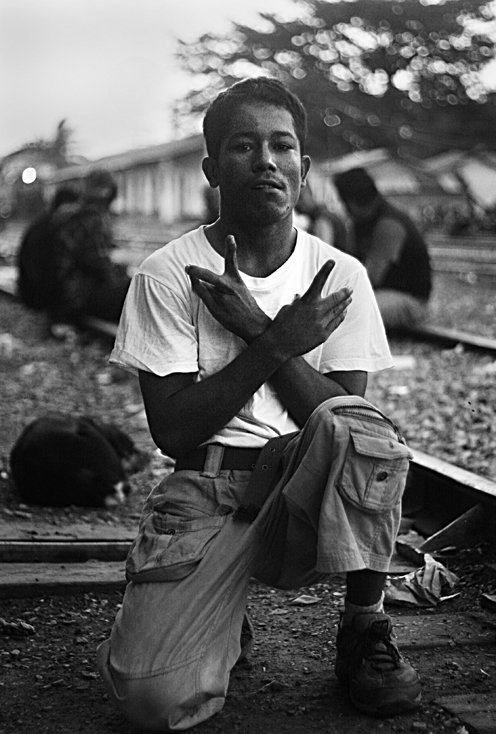

Along this corridor each migrant is prey to assaults, extortion, sexual abuses, kidnappings and murder perpetrated by a wide array of violent actors. This “mafia”—as the criminal apparatus is known in Ciudad Ixtepec, Oaxaca, a town renowned for constant kidnappings of migrants—is an amalgam of common criminals,maras, drug traffickers, and local authorities that often act jointly to exploit the passing migrants.

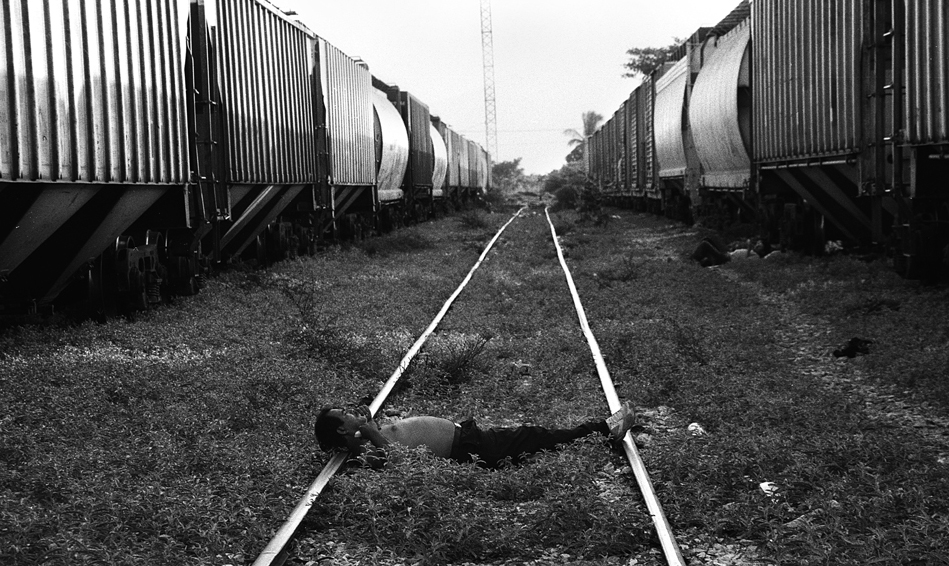

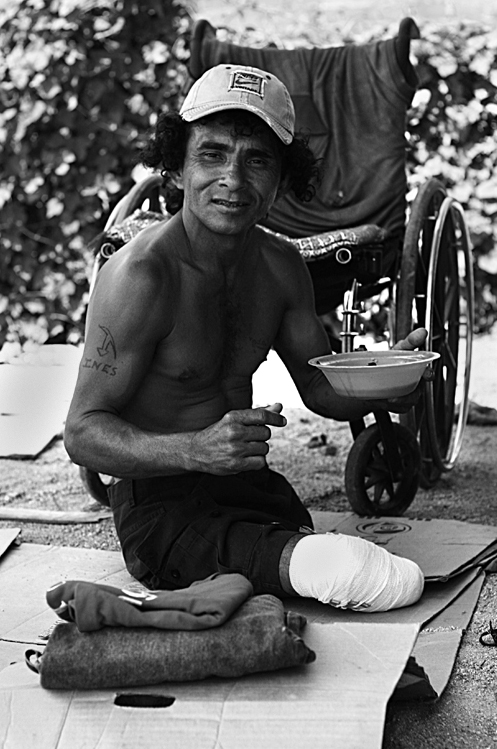

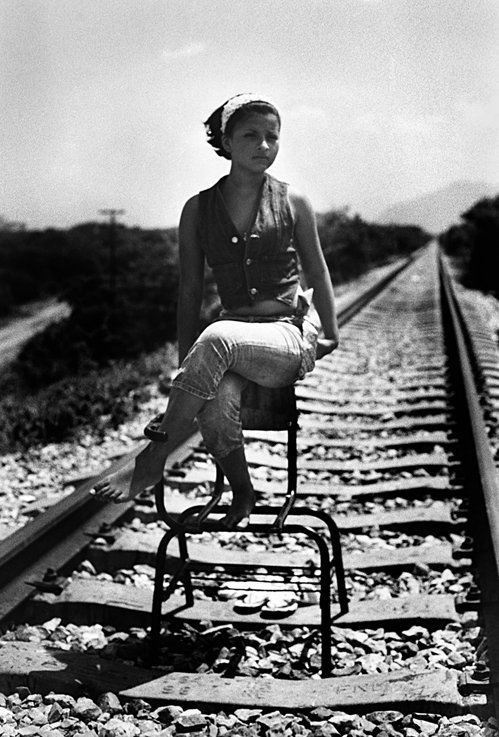

In addition to these atrocities, migrants endure the tremendous hardships of their grueling travel conditions. By not being able to move through roads or enter town centers, migrants are forced to transit through remote pathways and on highly dangerous means of transport such as double-floored trailers and the century-old cargo train that bisects Mexico. Migrants are often defeated by the trail: they die of asphyxiation in the double-floored trailers, or lose their limbs when falling off the train. The lethal nature of the voyage becomes palpable in the few shelters spread throughout the route that serve as sanctuaries for this violated population, most of whom will never get the chance to try crossing into the United States.

Thus, Mexico’s territory has come to represent an infinite mine field guarding the American dream, an unavoidable Vertical Border where abuse and suffering define the contours of the voyage to the North.

***

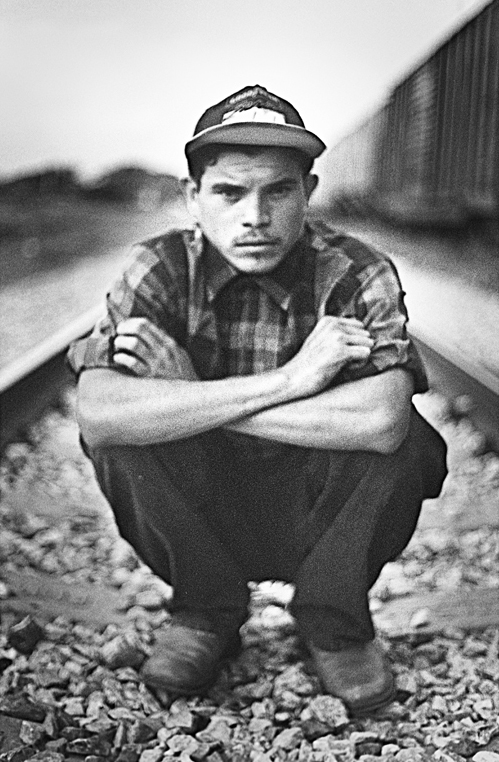

In the summer of 2007, I spent one of the most overwhelming and mystical nights of my life traveling on top of the cargo train. I scribbled a series of visceral notes, as I could not rationalize what I had lived through:

The sun began to plunge in the horizon. Exploding with orange, violet, and pink waves, that distant line that marked the beginning of the night spoke of calmness and peace, both of which I hoped existed with all my heart. At the same time, a heavy weight between my eyes reminded me that I knew it wasn’t so. The last two months of living in shelters along the migrant route had impregnated me with horror stories of killings, assaults, rape; of the crude and diverse suffering of the path. I was sitting on the infamous beast, on the train of death, with 10 hours to go before the next stop, clinging on to my camera and to a faith I had never had. I couldn’t let myself be taken away by the sweetness of the sunset. On the migrant route—and on the train specifically—you can never be sure who sleeps by your side, or when a military operation will take place, or if a band of maras will loot the train wielding machetes, or if the seasonal rains will cause the derailment of the wagons… An hour later, the century old locomotive huffed under a veil of stars. My adrenaline slowly paced down and a breath of air entered my lungs seemingly for the first time in the night. I found myself in that hypnotic state that I had all too often seen amongst the migrants: I was like a deer caught in the headlights, bowed down to my present, gagging my fears with a blind determination, taking refuge in the hope of a better tomorrow. The beat of my heart grew slow wanting to believe in the inherent goodness of human beings. Behind me, a young girl cursed her luck after meeting a migration police control on a highway in Chiapas:

“¡esos cabrones me violaron a mí y a mi prima! … seguimos caminando”.

“those bastards raped me and my cousin! … we’re still walking.”

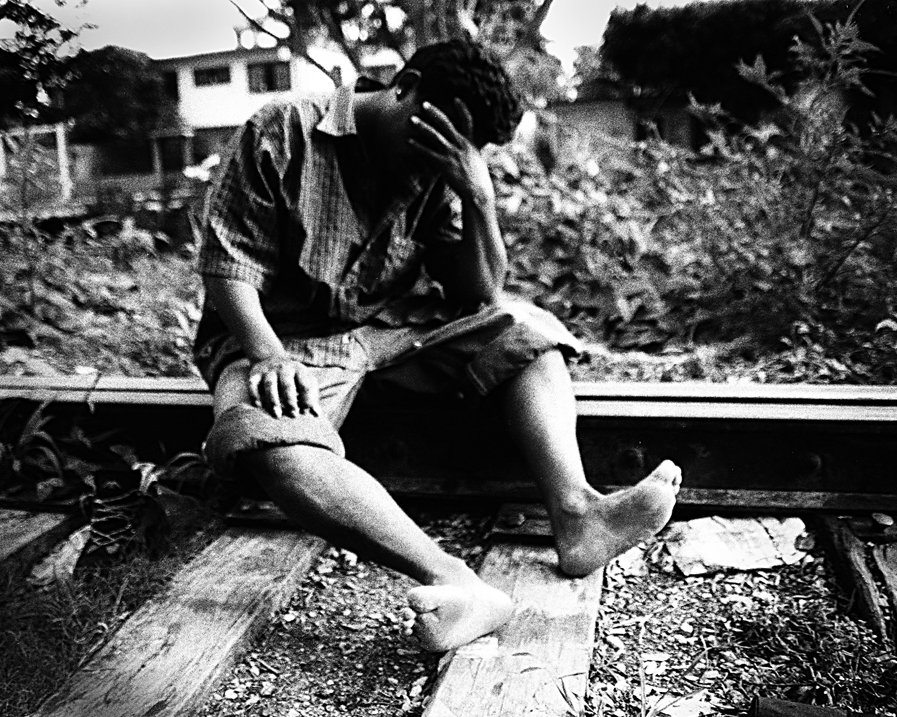

The migrant route is an infinitely obscure and complex place that cannot be measured with the same yard stick as the rest of society. The route is a sort of parallel universe ruled by its own logic and metaphysics. Here, the sense and value of life are incommensurably skewed. Up to what point is perishing along the way or being stripped of one’s dignity something to be expected? What is the internal psychological process of someone who walks knowing that he or she will be sexually abused? How can one continue living after being raped? How can a man continue after watching his wife get raped? What levels of misery and disenfranchisement make somebody hoist a sail toward this ordeal? Logic and reason do not hold the answers.

From a different standpoint, the Vertical Border is a capsule of anarchy that lies on the other side of the coin of order. The bloodcurdling accounts of the migrants belong to a Hobbesian dimension where violence is the only weight that counts. Unrestrained violence is a viral process that self-corrodes until it infects all life. Franz Fanon, in the crudeness of his masterpiece The Wretched of the Earth, illustrates the expansive properties of violence: in Algeria French colonial masters abused their Arab subjects; the latter then mistreated their wives; the wives then abused their children; and the children consequently used violence against their animals.

The same is true about the migrant route. The suffering that the migrants endure is inevitably framed within a broader structure of violence. As a vast survey led by the respected academic Rodolfo Casillas confirms, the locations with the highest incidence of human rights abuses on the route are in the poorest and most disenfranchised Mexican states it passes through: Chiapas, Oaxaca, and San Luis de Potosí. In these dismal locations, police have to buy their own uniforms and pay for their own weapons, while the average citizen struggles to survive. Given the complete and guaranteed impunity of any violence against migrants, it is not hard to understand why this systematic abuse takes place.

Yet the pervasive nature of violence does not take responsibility away from the Mexican state. In a subtle manner, violence along the migrant route is Mexico’s (and arguably the United States’) main method for deterring migration. The government’s strategy, through its actions and inaction, includes both the direct violence perpetrated by state agents and the indirect violence created by the marginalization of migrants and the assured impunity of any abuse perpetrated against them.

The problem with deterrence is that it corresponds to a logical framework of incentives and disincentives. The phenomenon of migration, however, simply does not operate on this frequency as reason and logic become skewed by the normalization of violence. Nancy Schepper Hughes’s seminal piece Death Without Weeping,for instance, shows how the normalization of violence has led people to justify something as brutal as that of the killings of street children in the Northeast of Brazil. In the case of the Vertical Border, the normalization of violence takes a particular dynamic as the temporary nature of migration forcibly influences the psyche of migrants. Since migration is confined to a discrete geographical space and time span, it is all too common for migrants to reassure themselves with thoughts such as “the worst part is over” or “it will all be worth it once we get to the United States”.

Several years after that bittersweet night on top of Mexico’s cargo train I’ve come to think that it is a true mystery—and a mixed blessing—how the basic human traits of faith, perseverance, fear, and nostalgia enable migrants to endure the abuses of the route…